by Stewart D. Roberson, EdD, President and CEO

Why do people ask questions? Generally, it’s because they want a better, deeper understanding of ideas or practices; and to get a successful answer, they ask someone who knows more than they do about the subject. Makes sense, right?

When a leading firm in K12 facility design wanted to know which school design features truly support learning, they quite reasonably asked the experts: those who do the work. They asked actual practitioners who had been trained to teach, who had teaching experience, and who demonstrated success as determined by their recognition as regional teachers of the year.

This is a story of how Moseley Architects, with support from Virginia Tech and the Virginia Department of Education, went about gathering their information and what they learned.

The Fellows

In February, Moseley Architects launched the inaugural Academy to Envision Tomorrow’s Schools and invited the Regional and Virginia Teachers of the Year for 2015 and 2016 to participate. The invitation generated overwhelming response as all 16 Fellows accepted the invitation to attend and participate in the Academy.

The Fellows came from all eight regions within the Commonwealth. They represented all school levels, with four representing middle school or middle school/high school combined schools, six representing elementary schools, and six representing high schools. Their curricular specialties at the middle and high school levels included agriculture, theater, English, social studies, and science. Early childhood, pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, and nearly all elementary grades were represented. Two of the elementary teachers taught students with disabilities as well. Eleven of the Fellows were female and five were male.

The Academy

The Academy began with dinner, welcomes, and a review of literature related to technology and facility impact. After an evening of setting the stage, the real work began early the next morning. Led by Moseley Architects, the Fellows began to brainstorm what 21st century learning was all about. Using the Gold Rush as an analogy, the Fellows were asked to do some idea mining around several questions. These brainstorming activities were important in creating common language and building rapport as the Academy moved toward its goal of identifying the essential characteristics of the school of the future.

The introductory question to which they responded was this: Considering descriptors of the ideal school of the future, what words come to mind? Descriptors, when analyzed, were categorized as follows: accessible, informal, exciting, flexible, safe and healthy, and student-centered.

- Accessibility related to meeting the needs of all students.

- Informal included casual and comfortable settings including the outdoors.

- Exciting related to the energy for the students, the displays of student work, and the physical design.

- Flexible included the ability to open and close settings for multiple uses and for future needs, access and use by the community, a variety of spaces, and spaces that were appropriate for curricula.

- Safe and healthy included a sense of both emotional and physical safety, a physical climate that includes natural lighting, appropriate color, and climate control.

- Finally, student-centered encompassed all the other categories that provide guidance on a variety of gathering spaces, flexibility and responsiveness to student learning, and attention to the safety and health of students. It also included the coaching strategies that allow students to discover new knowledge and relevant challenges that become lessons, and books and other interesting and informative media that are distributed in multiple locations.

The next prompt required the Fellows to respond with verbs regarding activities happening in an ideal future school. Those responses were analyzed and fell into several 21st century skills categories: communication, creativity, critical thinking, media skills, and life skills.

- Communication included words like writing, apologizing, connecting, debating, disagreeing, communicating, and yelling. When students can communicate and exchange ideas, they learn and build relationships that can expand their perceptions of themselves and the world around them.

- Creativity was associated with words like exploring, designing, pretending, and imagining. In a world that is changing rapidly, and growing smaller as it does so, being able to consider what could be is as valuable as considering what is.

- Critical thinking encompassed thinking and questioning, analyzing and assessing, trying and failing, risking and reflecting, learning and experimenting, recalibrating and evaluating, and finally, synthesizing and critiquing. All those skills are essential in making appropriate decisions.

- Media skills could also have been considered within communication as the Fellows threw out words like filming, texting, blogging, and skyping. In each case, they indicated skills related to technology and skills related to effective communication.

- Finally, life skills seemed the most appropriate category for words like resting, meditating, inaugurating, eating, and playing. Effective schools for the 21st century would prepare the student to live well through effective communication, creative and critical thinking, and learning how to live in a technological society.

On a lighter note, at least one participant suggested that Moseley Architects would design the building!

The final idea-mining prompt required Fellows to shout out adjectives in response to the prompt, “Our ideal learning environment will be successful when it can be…”

In response to this prompt, Fellows provided adjectives, which upon analysis, could be identified within the themes of relational, academic/instructional, safe, flexible, and other physical characteristics. Almost half of the responses could describe the physical characteristics of the school building, but the remaining adjectives were more reflective of the teachers’ roles and responsibilities. For example, within the theme of relational, the adjectives included playful, engaging, inspiring, personalized, honest, and inviting. Likewise, within the theme of academic/instructional, Fellows mentioned challenging, varied, responsive, agile, interactive, age appropriate, and multi-sensory. Flexible included terms like dynamic, open, multifaceted, and connected, while safe included equitable, and clean. The theme of other physical characteristics represented concepts like colorful, spacious and airy, realistic and natural, stimulating – but not too stimulating, bright, modern, and accessible.

The responses and themes generated in these warm-up activities indicated that the Fellows were already addressing the identified skills and needs of our 21st century and beyond learners. This validation of their expertise gave additional value to their responses related to buildings of the future, the primary focus of the remaining Academy activities.

Designing the school of the future

As the day’s activities continued, architects worked with the Fellows in small groups to focus the discussion on the building needs for future learners and their teachers. One group was comprised of high school teachers, one was comprised of elementary teachers, and the final group was comprised of middle school and combined middle/high school teachers. The discussions were guided by a series of questions that addressed 21st century skills, classrooms and beyond, flexibility, technology, and furnishings.

As the Fellows’ comments were collected, reviewed, collated, and analyzed, seven broad themes were identified. Those themes were student-centered design, collaborative spaces, flexibility, technology, extensions of the classroom, media centers, and buildings that teach.

Student-Centered Design. How did the Fellows see a building that was student-centered? There was a discussion at the table of high school teachers related to interdisciplinary versus departmental layouts that allowed for consideration of both designs as they relate to a design that focused on students. They indicated that either format could be effective if it considered the needs of the students. An advantage of interdisciplinary design is that it effectively creates a smaller learning community for students and the opportunity for more integrated lessons through collaborative discussion among faculty members. Other Fellows, at the elementary and middle levels shared ideas related to the neighborhood feeling among grade levels using color and themes to break down the scale of the school by grade.

Displays were valued to ensure a student-centered design. Spaces for dedicated public art that could be expanded by students “on a whim” were identified. Having additional spaces for displaying art work and other student work was also noted as an intentional design feature. The ability to share not just traditional, but also multimedia, 3D, and models was important to the group.

Fellows shared that they valued a variety of space types and sizes that allowed students to have social and dining settings that encouraged them to continue their learning beyond the classroom. Individual workspaces outside the classroom were also noted as important for student reflection and independent study. The Fellows also indicated that students needed spaces for hands-on learning. All these descriptions pointed toward providing a more individualized and personalized experience to meet the various needs of all the students.

Collaborative Spaces. Within this thread of the discussion, the Fellows shared their belief that transparency is necessary. The ability for teachers to see beyond their spaces and for students to see into spaces was an opportunity to showcase learning. It would provide, as noted, a passive level of supervision.

To develop common or integrated lessons and to expand their own learning, teachers and students alike need collaborative spaces. They suggested expanded spaces where two or more classes could meet for extended learning. Other recommendations included spaces that could expand learning beyond the classroom space, with or without furniture.

Flexibility. Flexibility, as a theme, addressed the built environment as well as the furnishings within. Because of the need to be flexible within identified spaces, Fellows suggested furniture that was movable and stackable. Because of the variety of activities that support learning, the configuration of the classroom should be flexible enough, they noted, to support those activities. The ability to rearrange the furnishings to meet instructional needs also included the ability to open – or close – walls, in response to those needs. Having movable and easily operable walls allowed for larger or smaller group activities that could be configured quickly.

Mobile technology was also included within the theme of flexibility. As the classroom becomes flexible, the ability to move the smart board or other mobile technology in response supports the instructional needs of students. Further, it was noted by Fellows, that every surface could then be a teaching wall. One participant talked about writing on all the surfaces, including the glass walls and windows.

Technology. While improving mobile technology has already been discussed within the theme of flexibility, the use of technology was expanded by the Fellows to include the ability to monitor student activity as they moved beyond the classroom to any number of informal learning spaces throughout the school, indoors or out. The Fellows suggested the use of video monitoring and communication devices for those extended learning spaces. They also suggested an increased ability to use voice amplification, especially in larger spaces. Fellows wanted to include the ability for teachers to communicate with each other, perhaps through Bluetooth technology, so that they became closer partners in student learning. Fellows also discussed expanded learning opportunities for students through interactive technology or video walls.

The discussion of technology continued as teachers saw the need to decrease restrictions on the use of personal mobile devices within the school. They indicated the value of using individual devices to share specific information with students in a variety of ways.

Media Centers. Discussion that focused on media also included considering if a media center was necessary. Fellows, however, believed the media center could easily become another informal classroom, with a Barnes and Noble environment. They indicated that the space should incorporate technology and texting. They described the space as one that should be student-centered, a space that students would want to occupy. Comfortable seating was important. Fellows mentioned the possibility of the library as an extension of the cafeteria. While they believed that technology should be readily available, they also agreed that the technology should not replace books.

Buildings that Teach. The final theme included ideas about how a building becomes a part of the student’s learning. One example was providing outdoor spaces that could be used for gardens, which Fellows mentioned as valuable to art and science. Outdoor classrooms were also discussed, both rooftop and ground level. They also noted that the building’s efficiency should be displayed through dashboards, for example. Even the ability to measure rainfall was part of the discussion.

School Designs

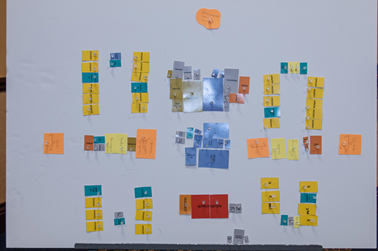

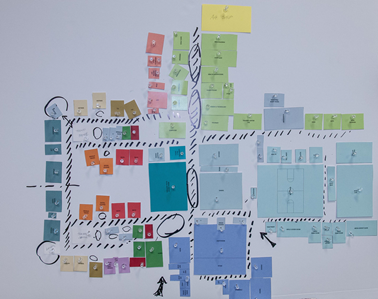

This inaugural Academy to Envision Tomorrow’s Schools generated more than the discussions of the seven themes. Fellows also created visual representations of those themes as architects and designers of schools might apply them.

Elementary School

The elementary team identified learning areas, including outdoor learning spaces for each grade level (Figure 1). Administrative and student services were centralized, and collaborative areas were planned for each area

Middle School

The middle school team provided integrated learning and collaborative areas for each grade. They also placed STEM activity and other learning labs adjacent to the media center and planned outdoor seating and learning spaces (Figure 2).

High School

The high school team identified multiple informal seating areas for students to work individually or collaboratively, as shown by the black ovals and circles in Figure 3. They also integrated the core curricular areas.

Participant Reflections

After the completion of the Academy, Fellows expressed their excitement that their “teacher voices” were both sought and heard. They further indicated how much they appreciated the opportunity to work directly with architects to talk about both the curriculum and the physical design of future schools. Fellows said that what they learned would encourage them to continue to provide learner-centered and personalized instruction and to arrange their classrooms, investigate other furnishings, and encourage their professional colleagues to expand outdoor opportunities for students. Overall, the Fellows continued to express strong satisfaction with the format, the timing, and the experience.