Lessons learned from two decades of sustainable design and energy efficient buildings

by John Nichols

Building owners are frequently challenged by limited budgets for new construction, major renovations, and ongoing maintenance. They also have unique opportunities to improve energy efficiency and reduce life-cycle cost, given that many of these buildings will operate for 50 years or more. So, how can building owners maximize these strategies while still working within the realities of budget constraints?

Step 1: Start with the end in mind

The first step to improving your buildings’ energy performance is thinking about where you are now and where you want to end up. This is just as important for existing buildings as it is for new construction.

- Benchmark against your peers. Start by asking your energy manager or an outside consultant to run a report showing how your buildings’ energy use stacks up against other facilities of the same type. Benchmarking programs like ENERGY STAR® are especially helpful because they provide you with a 0-100 score that measures how your buildings compare to others on an apples-to-apples basis.

- Set a specific goal or target. Setting a goal, even if it is aspirational, motivates the entire team and gives you the right context for evaluating design decisions. Be as specific as possible; targets like Energy Use Intensity (EUI) or a carbon reduction goal give more direction to the project team than generalities like “green” or “sustainable.”

- Harvest the low-hanging fruit first. Geothermal wellfields and solar panels tend to be the first things people think of when it comes to saving energy. While those systems are important, there are hundreds of other strategies that can be even more cost-effective. Identify the payback period and upfront cost you are comfortable with and ask your project team to recommend strategies that meet those parameters.

Once you have an idea of how energy efficient your current buildings are and how much you can improve, charting your path becomes considerably easier.

Step 2: Don’t just coordinate—collaborate.

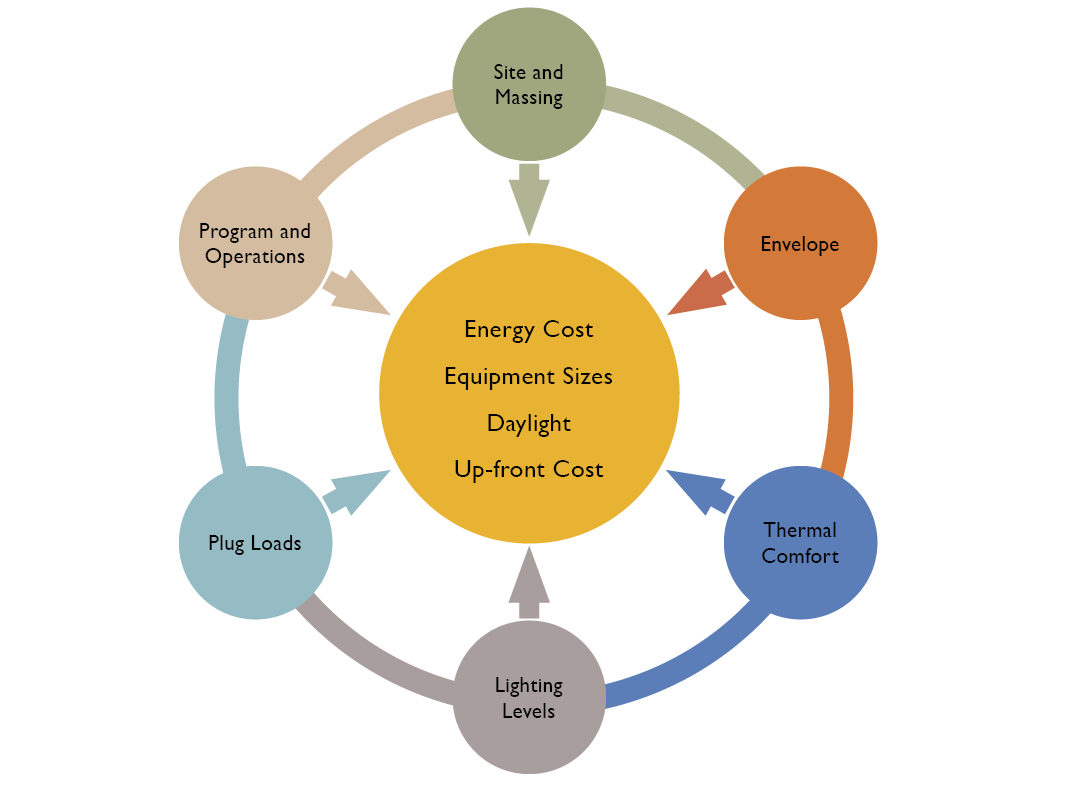

Now that you have an idea of your starting point and your goal, it’s time to involve the right team members to help you connect the dots. The best way to do this is through an integrated design process. Gather your architects, engineers, maintenance staff, and other stakeholders in a collaborative workshop to talk about your energy goals and possible strategies. By asking each other questions and exploring alternate approaches, team members often uncover strategies that reduce both upfront capital costs and long-term costs. Here are some examples:

Better glass = smaller HVAC. Most window upgrades have a considerable upfront cost, but if your engineers know what is being considered, they can usually decrease the size of the HVAC components. Doing so can greatly improve the payback, or even pay for the window upgrades outright.

Brighter finishes = less lighting. When interior designers and electrical engineers collaborate, brilliant strategies to reduce upfront and long-term costs come to light. Bright, reflective interior finishes not only improve the aesthetics of your space, they can also decrease the number of light fixtures needed to illuminate that space.

Step 3: The envelope please…

Once you’ve engaged your project team in a collaborative design effort, the next step is to focus your collective attention on the building envelope. This is especially true for local government teams, where most building envelopes need to last 50 years or more. Careful consideration of the building envelope is especially important on new construction but should also be part of major renovations. Some prominent items to remember:

- Use the correct amount of insulation. Existing structures with poor insulation can benefit greatly from adding even just a small amount of insulation. On the other hand, new buildings don’t typically benefit from having more insulation than the minimum required by code. This is especially true on larger buildings, where too much insulation can trap excess heat inside, so it becomes necessary to sometimes use the air conditioning, even during the winter months!

- Choose the right windows. Good windows are building envelope “All-Stars”. But many variables contribute to whether windows are “good”. Ask your mechanical engineer to run a building energy model to determine the right type of windows for your buildings’ use, size, and solar orientation. “Spectrally selective” glass is especially useful since it maximizes daylight while minimizing solar heat gain.

- Combat WAV-T. A properly designed air barrier system will address WAV-T issues – Water, Air, Vapor, and Thermal – which are the most important concerns for building envelopes. One of the best paths to success is to simplify the overall complexity of the building envelope by reducing the number of joints and intersections between materials.

Step 4: Heat it, cool it, light it.

After thinking through the best ways to design the building shell, it’s time to discuss everything that will go inside the building. To save energy and ensure the comfort and wellbeing of your building occupants, it is crucial to choose the right technologies for heating, cooling, lighting, ventilating, and performing all the other processes that support your building.

- Go for high(er) efficiency. Energy-saving HVAC components are available for every possible system type, not just geothermal and chillers/boilers. Ask manufacturers for high efficiency options and variable frequency drives (VFD) for everything from pumps and fans to compressors and furnaces.

- Keep it simple. HVAC and lighting controls are one of the most cost-effective components for saving energy, if the number of sensors and signals don’t become overwhelming. Work with your operations and maintenance staff to identify the right balance between automated and manual controls and make sure they feel confident maintaining the proposed equipment.

- What (or who) are you forgetting? While HVAC and lighting systems typically consume the most energy in a building, other systems such as domestic hot water, foodservice, and IT equipment are sometimes overlooked. Ask your engineers and vendors to specify ENERGY STAR models for these systems and propose other energy-saving options like add-on devices that recapture waste heat.

have an estimated payback period of fewer than five years.

Step 5: Check your work.

You’ve successfully gone through design and construction; now you’re moving into operations. Congratulations! But as with many things in life, your work is never truly finished. Here are the next steps for ensuring that your buildings operate the way you intended and for applying what you have learned to future projects.

- Commissioning is a must. Building commissioning became popular as LEED® gained traction in the marketplace, but its value isn’t limited to green buildings. Engaging a quality commissioning agent can easily pay for itself by making sure everything is working as it should. On existing buildings this is often the first step to diagnosing issues and setting goals.

- Track your progress. Remember those energy goals we set back in Step 1? As the saying goes, “you can’t manage what you don’t measure.” Annual reports showing the Energy Use Intensity (EUI) of each building are a good start; evaluating your energy use monthly and by fuel type will help you identify anomalies and address them as they occur.

- What worked? What didn’t? Projects end as new ones begin, but no building is truly “complete” when and technology change over time. Developing an internal knowledge base and sharing your experience with project teams are invaluable ways to repeat the strategies that worked and avoid those that did not.

This article originally appeared in the March 2021 issue of Virginia Town & City. Its author, John Nichols, served for 15 years as a sustainability coordinator and later as the director of energy analytics and informed design at Moseley Architects.